How to play classical mandolin:

Learn scales & arpeggio techniques?

By Jean Comeau

Why bother with mandolin techniques? That is the question…I spent thirty years of my life teaching in high school. I read about everything I could find on the art of teaching. But I must admit that once in a while, some situations still make my jaw drop. Recently, a music teacher told me that almost all of his students were unwilling to play technique works, exercises, scales, etudes, etc. And what most amazed me was to hear that it was adult students who were the most reluctant. On top of that, what really stunned me is that, apparently, teachers don't insist! They don't want to loose their students!

If someone thinks he can cut short his learning by working solely on "songs" and avoiding technique, he is the perfect candidate to become an early dropout. He will very soon get tired of knocking his head on the wall and will succumb to his limits.

Like every type of learning, playing a musical instrument involves a lot of skills acquired during years of daily practice. The number of skills is limited, the nature and the number differ from one instrument to the other, but acquiring these skills always takes time and it's generally tedious; that's the way things are and there's very little we can do about it. Those who claim the contrary are usually more interested in profits than teaching.

We should never forget that the pieces we play are nothing else but a specific organization of techniques. Let's look at a piece that is far from easy, the Rondo op. 127 from Calace.

If we coldly analyze this piece, like any other, it's nothing but a specific organization of different techniques. Let's look at what's involved in this Rondo.

The beginning of the piece requires a good mastering of the different picking techniques; we must choose between downstrokes, upstrokes or alternates; many grace notes involve the mastering of pull offs if we decide to play them this way.

When the piece changes to D minor, we must have a good, soft and steady tremolo; when it comes back "in tempo", fast changes of course might be problematic. The last staves of the second page implies a good arpeggio technique. A little further, the composer asks for fast double-picking on high notes which can easily become pretty messy if our double-picking is weak. At the end of the piece, we play the theme once more but in tremolo this time, and then, a series of loud chords marked fff must be played very clearly, very precisely, otherwise it can easily sound pretty ridiculous.

Such a piece may be considered extremely difficult, especially at high speed. However, regardless of the speed, if it gets confused, it's generally because one of our technique is weak. And even if with such a weak technique we manage to get through, the problem will recur later in another piece. It's like the Groundhog Day movie. The problem is in no way solved.

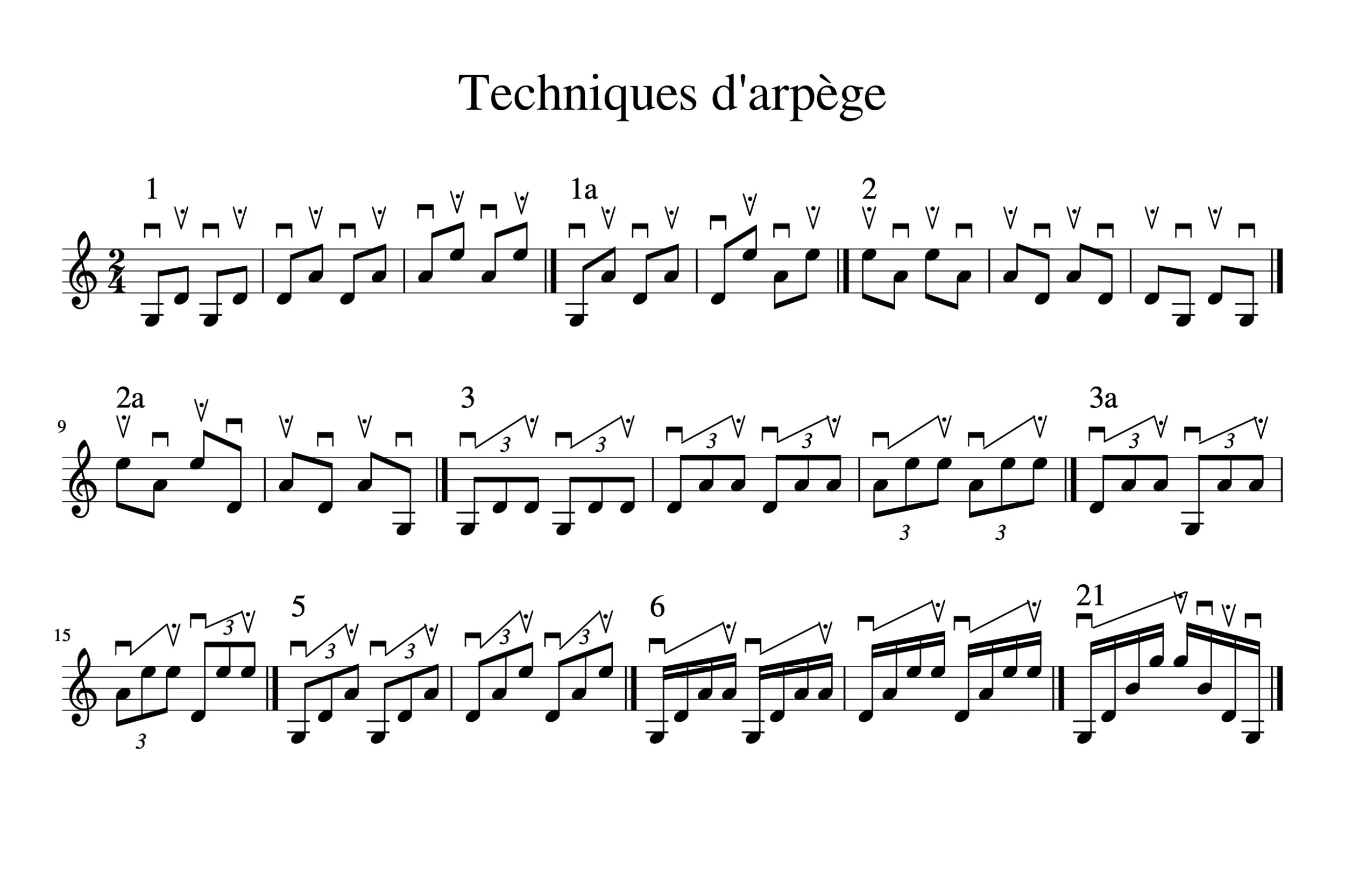

Learning a musical instrument is a lifelong achievement. We never completely possess all the techniques. If someone looks for an easy way to play an instrument, he looses his time. Even playing the triangle can get unexpectedly messy! But there are so many tools to improve our technique! Let's take the arpeggio passage in the Rondo. As early as the XVIIIe century, a whole lot of exercises were written in that style, namely Pietro Denis' Preludes. Later, the Romantic era considered the arpeggio techniques as one of its most brilliant ways of playing. We can find many exercises in every good modern mandolin method. Using Denis' Preludes, Marga Wilden-Hüsgen listed at least 25 variations of arpeggiated passages.

Here are a few examples:

Learning to master all the arpeggio techniques takes years of practice.

But there is far more! Learning a technique doesn't help mastering another one. Someone can play scales at a breathtaking speed without being able to play a decent tremolo; if we can easily align a series of chords on four strings, it doesn't mean we'll be able to play them in harp-arpeggio; being able to play in duo-style (tremolo-staccato) doesn't make us competent in combining tremolo and pizzicato. You get the point.

Also, we must not forget that every technique must be mastered in every situation: playing in tremolo is something, but playing a soft, fast and regular tremolo on the G string is something else; tremolo sul tasto or sul ponticello might be rather tricky; playing a soft tremolo with changes in speed or dynamics needs a lot of practice; playing measured tremolo is not at all the same as playing unmeasured tremolo; properly starting and stopping a tremolo needs special attention; we don't play a tremolo in seventh position like we play it in first; double stop tremolo can become a real nightmare. And we must not forget that tremolo is only one technique among many others.

So, how can we expect to master our instrument by learning "a song at every lesson", like we are proposed to in so many music school advertisements?

Jean Comeau for Mando Montreal

Jean studied piano in his childhood and was addicted to Chopin's concertos. He also studied serial composition, flute, organ and singing. During his career as a french and theater teacher in high school, he founded the Bateleur's theater company for which he has written, composed music, made costumes and builds sets for 17 years. Now retired from teaching, Jean devotes himself full time to his passion: the mandolin